Ideas For Future Posts

/Future Post Ideas

It looks like I will be cutting back on the time I spend on writing blogs posts for a while, so I thought I would outline some of the ideas I have for future posts. Just so you know I am thinking of you.

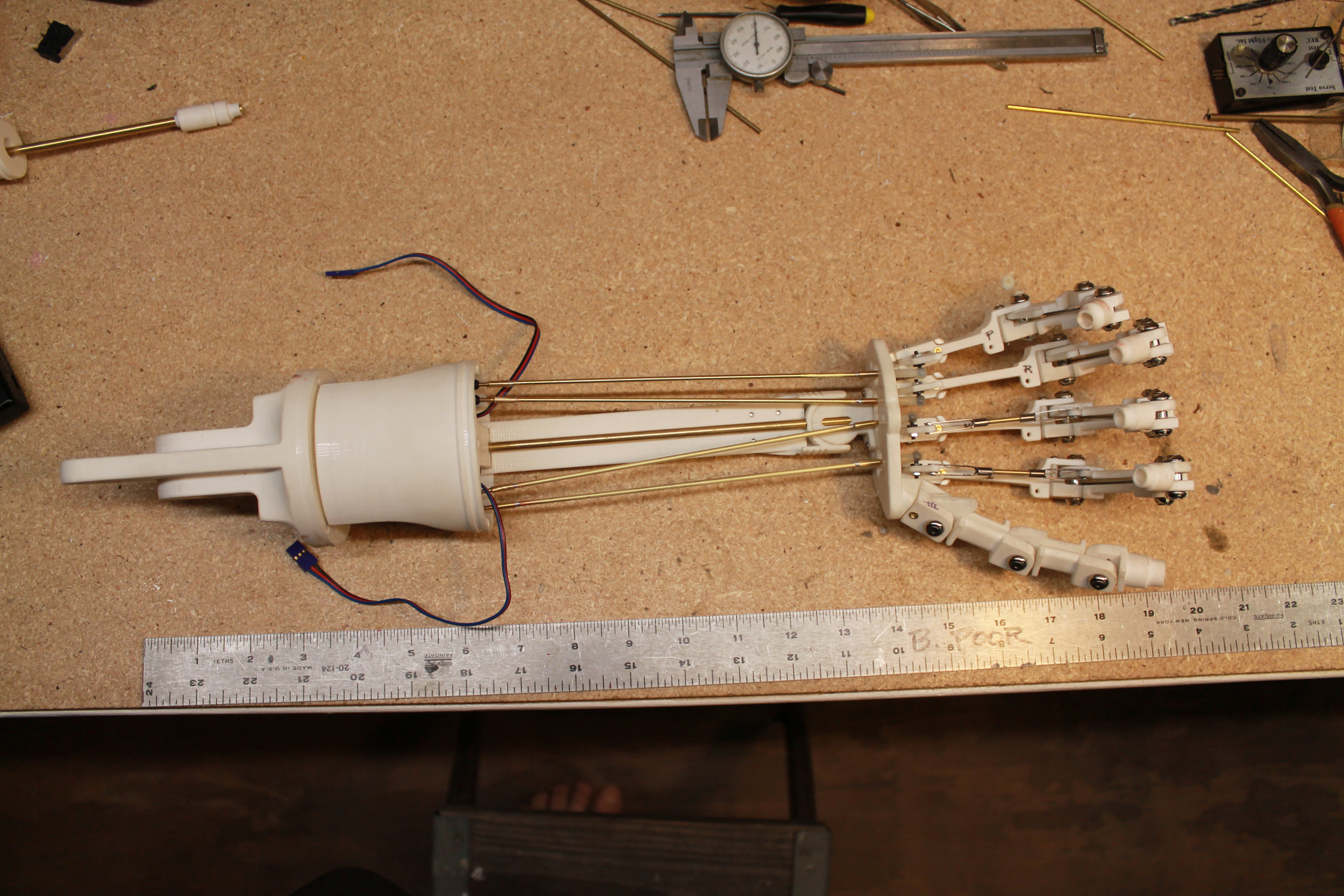

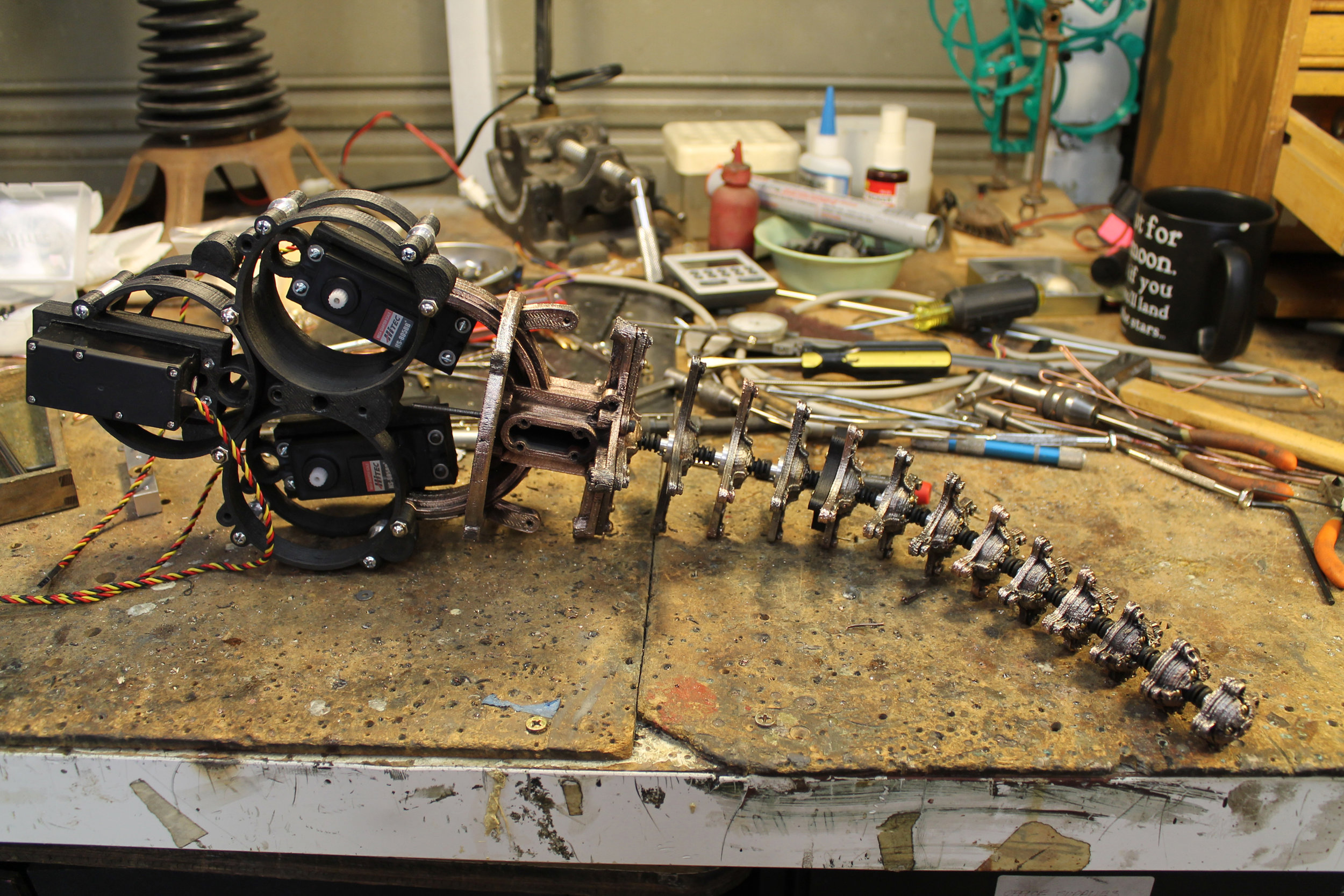

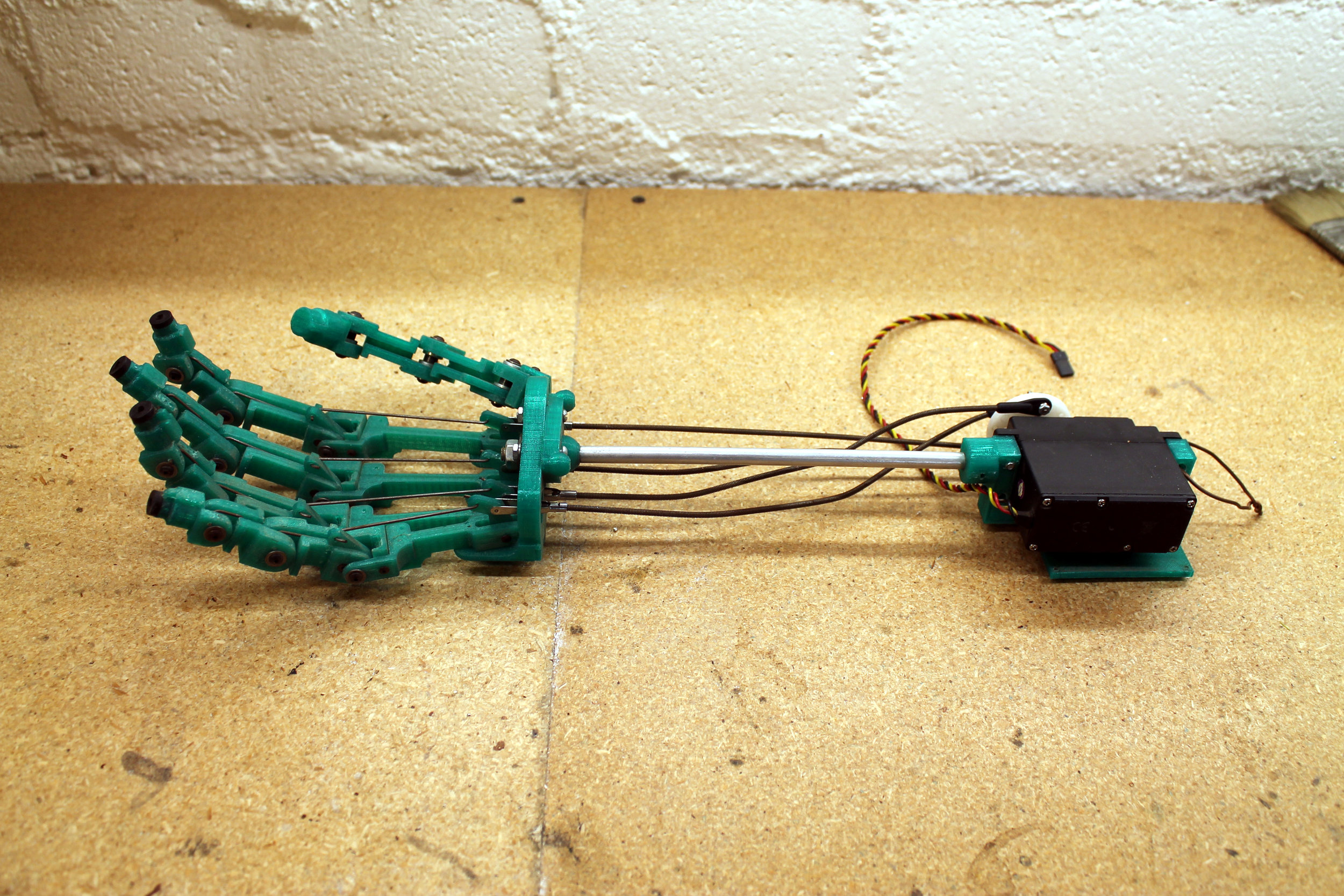

Self-Propelled 3d Printed Terminator Hand

This is a mash up of my 3d printed Crawling Terminator Hand, from six or eight posts ago, and the Endoarm posted to Grab Cad by Simo83. Simo83 saved me a huge amount of work by creating a beautiful model of the classic Terminator Arm and posting it online. Yay for Simo83.

https://grabcad.com/library/endoarm-stl-1

I modified the Endoarm design by making the fingers mechanically functional and then 3d printed the whole thing up in order to create a replica of the T-800 Terminator arm capable of dragging itself along by its fingertips.

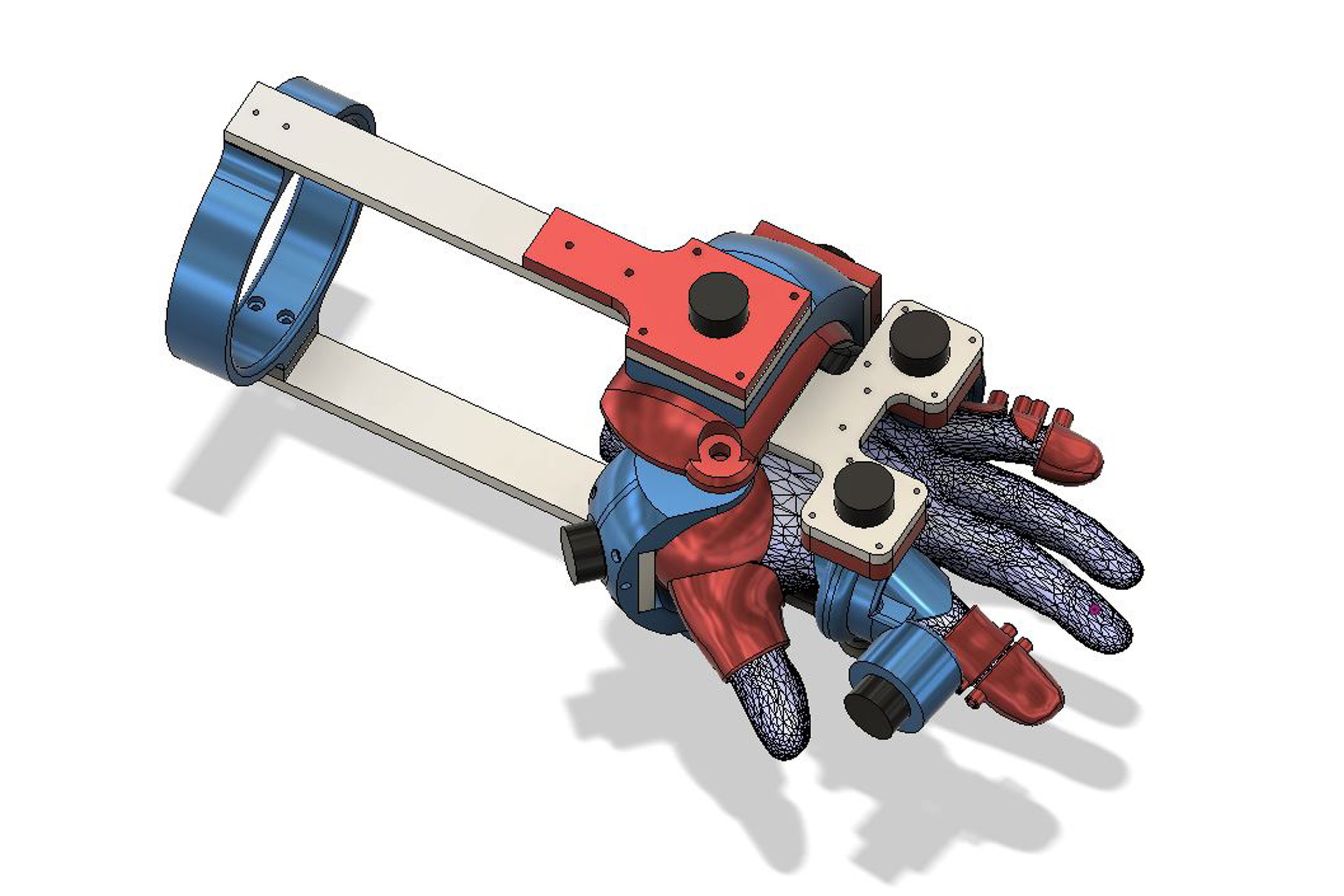

3d Scanning and Working With Scanned Data

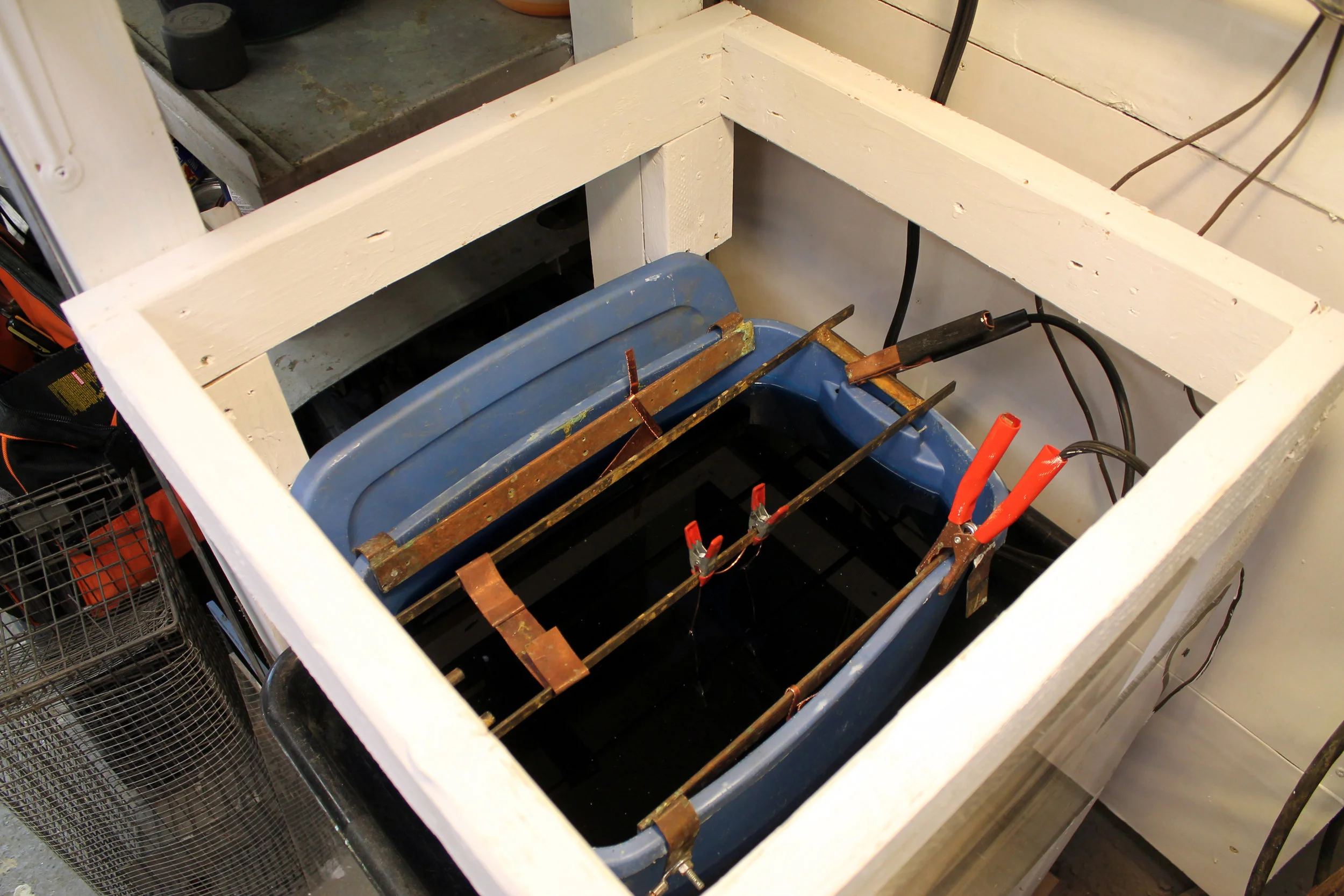

I got myself a 3d scanner awhile back and put it through its paces to see what it could do. It could do quite a bit until it stopped working just as its warranty had expired. That’s what I get for being an early adopter but I learned a lot. I will demonstrate the process I went through to create a 3d model of my hand and how I was able to use that data to create a custom fit, 3d printed Telemetry Glove.

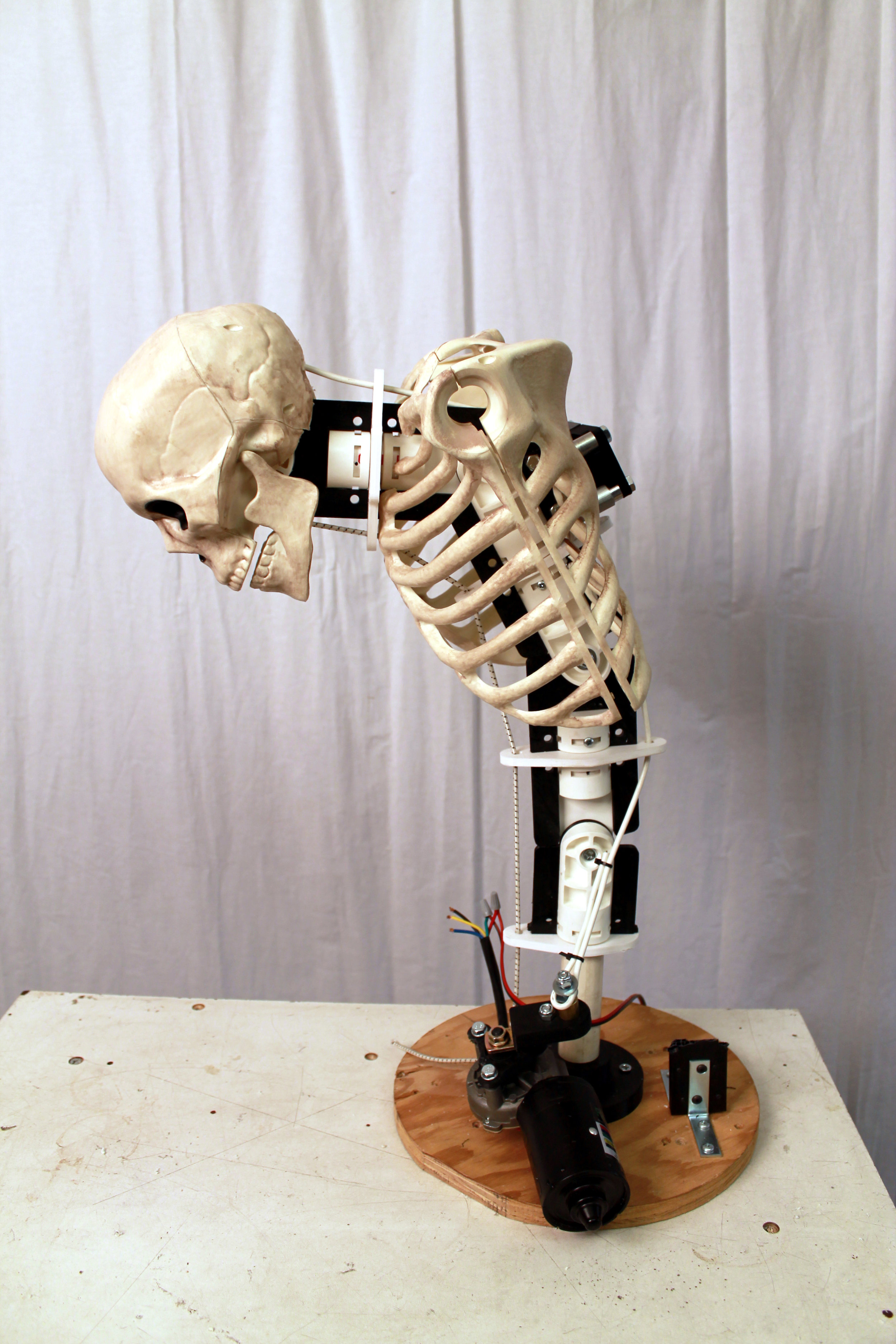

How To Film Animatronic Puppets

The use of practical creature effects for film and television has become so “old-school” that there is a whole new generation of filmmakers who don’t know how to best utilize it. I am going to create a primer on some of the basic techniques involved in the process of filming the performances animatronic puppets.

A few years back a videographer friend of mine and I made a short film featuring animatronic puppets called The Escape. A wide range of techniques came into play during filming and I am going to deconstruct the whole process and explain how all the various shots were made to work.

Stay tuned!